Lubomyr Melnyk

Lubomyr Melnyk - The World's Fastest Piano Player

The world's fastest piano player

Lubomyr Melnyk is the world's fastest pianist, with a stunning performance style he calls "continuous music"—so why did it take 40 years for his music to be heard? Matthew Bennett tells his story

First published in Resident Advisor

March 2015

Lubomyr Melnyk is a 66-year-old Ukrainian pianist who for the last 40 years has been trying—and failing—to bring attention to his work. He spent that time becoming the world's fastest piano player. Since 1968 he's been pioneering a style of "continuous music," a mesmeric technique that is only now gaining recognition in experimental circles. Melnyk unfurls hour-long odysseys into the epicentre of melody, with an average speed of 12-14 notes per second—for each hand.

Melnyk nearly died of starvation developing his radical piano system, only for the classical establishment to dismiss his work. After decades of being ostracised his anger threatened to consume him. "For a long time I was deeply broken-hearted," says Melnyk after I finally track him down in Tokyo, at the Red Bull Music Academy studios on a sunny November afternoon. "The classical music scene did not like my music. Like we can't hear a dog whistle, the classical establishment did not want to hear nor could fathom my music. I was really sad for years."

His epic works, such as "Windmills" and "Pockets Of Light," are melodious torrents of notes that move so fast they're overwhelming. His music brings to mind acts like Autechre, Battles and 65Daysofstatic, who bombard your mind into a meditative state through endless complexities. So why are we only hearing Melnyk's continuous music now? And why do his sublime piano pieces make sense in 2015? In order to answer these questions, it's necessary to go back to the late '60s, to the start of his agonised journey.

"A lot of us ambient composers owe a debt to 1968 and 1969," says Melnyk, who is clearly savouring being interviewed. "We owe a debt to Columbia Records, who released Terry Riley's 'In C.' This blew everyone's minds right off the planet. You can't imagine what that was like back then as you've grown up with its influence."

As "In C" emerged like a minimalist storm, Melnyk fully embraced it. "In C" set him onto a brave new course, and Melnyk was ready for the challenge. He was living a simple life as a hippy in Paris, enjoying an interest in philosophy and LSD. "You ask me: 'What was the light bulb moment going off when I conceived continuous music?' But 'In C' was really the light bulb moment going off! That album gave rise to Steve Reich and gave rise to Philip Glass, it started a chain reaction of musicians and it just struck a chord inside our hearts and inside our souls."

Unlike Reich, Melnyk didn't have the luxury of eight or 20 musicians to play his freshly imagined pieces. He was penniless. He could hardly feed himself. He did, however, have access to a piano and he started playing, combining the influence of Terry Riley with his classical training.

This was where the hard work started. Melnyk is keen to point out that his continuous music required two significant skills, which evolved over two years. Firstly, the mental ability to write and recall songs that across an hour of recital can include nearly 100,000 notes. Secondly, he had to develop the physical capacity to play pieces that last up to 45 minutes. His technique has clearly affected him: when Melnyk talks he unconsciously toys with the tendons on the back of his hands.

The Ukrainian references the Kung Fu masters to explain the zone he enters when writing and reciting his pieces. "You ask: 'Is it a state of mind?' It is not. It's a state of the body. The Kung Fu master can perform incredible feats because his body has disappeared. The master's body is almost like a translucent ghostly aura of energy and he is simply manipulating it." There were other influences on the man: "When I see Jimmy Hendrix play the guitar I understand totally," he says firmly, "because he's there where the Kung-Fu masters are.

"Then I discovered people like John McLaughlin and Ravi Shankar. Suddenly there were all these philosophies of musicianship. I could hear the complexities of their music and marvel at the fact that their minds were controlling and counting all of these beats going from 14 to 26 note cells and I realised that if they can do it then so can I."

Melnyk was so poor in Paris that he nearly starved. He admits that he would weave around the streets at dawn foraging for discarded vegetables. Were his piano experiments a refuge from his hunger? "It was, yes. It was very strange. It was like God made sure that I had enough food to survive. As we know, the more you eat then the more asleep you become. My physical state back then was very conducive to become closer to a state of meditation, and I could feel the inner workings of my body changing. That was very crucial to learning the technique. I would never have gone there if I wasn't in that state of hunger. I remember I was so starved some days I would be hallucinating watching the sunset."

A further founding tenet of continuous music was Melnyk's philosophy studies at university. He describes how the ideologies of P.D. Ouspensky, a Russian mystic philosopher from the 1880s, shaped his understanding of the universe. Ouspensky taught Melnyk how to reach a philosophical plateau where his existence attained greater meaning and substance. It was the final piece of his personal jigsaw. "If you took away Paris, if you took away the hunger, if you took away the hippy, and if you took away the philosophy, then there will be nothing left in which the seed of continuous music could grow."

But the world was not ready for Melnyk's unique seed. When we discuss the industry's response to continuous music he becomes sad, a feeling that takes him back to Kingston, Ontario in 1974. "OK, this is very interesting," he says in pithy resignation. "You have to ask about the first and second bits of press. One professor heard it and he wrote an amazing thing: 'It is almost as if the piano was always meant to sound this way.' This man is 55-years-old, he was a classicist but he could hear the delicacies and all the intricacies of it.

"Then I did a performance somewhere else. And so came the second review: 'Who let this idiot on the stage?!' and, 'Melnyk's music isn't even boring, his music is painful,' or, 'Dear public. Stay away from this man.' This was the second review. And that review, I'm sad to say, became the most prominent."

These critiques signalled Melnyk's eventual banishment from relevance or exposure. He envisioned his revolution in 1968; he claims his audience only arrived after he debuted on the Erased Tapes label with the 2012 release of an album called Corollaries.

"Oh yeah!" he smiles. "People wonder why they had never heard of me and my music. I was hidden away from the world. There were budgets to play concerts between 1974 and 1985, but there might only be 20 people there. But from 1985 until 2012 there was almost nothing. So I was starting to get quite angry with the classical world. I felt that my music was a true development of classical music. It's very difficult to play, it has an extremely high level of pianistic virtuosity. What is there not to like?"

It appears Melnyk fell so neatly in the gap between modern classical and minimalist avant-garde that no one cared. His lightening fast piano works, especially the 45-minute "Windmills," at points can appear dissonant when compared to more spacious, pretty piano works. But minimalism often works best when it's rough. His style is a remarkable feat in physicality, endurance and vision of sound. He just had to wait for recognition to fall upon him.

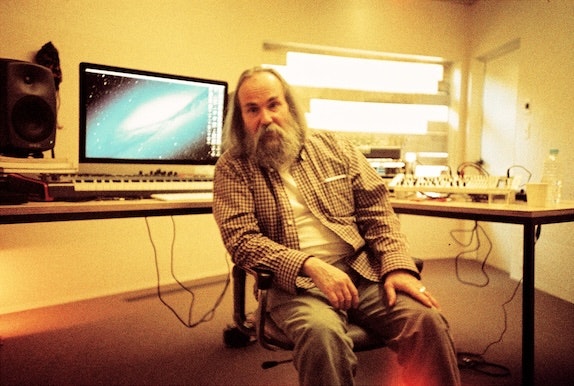

Melnyk is clearly surprised that it's a younger generation, mainly from an electronic music background, who are the ones now attending his concerts. We conduct our interview at the Red Bull Music Academy surrounded by the modular synths and controllers favoured by the modern establishment.

His long sought recognition finally happened in Cologne after Melnyk connected with the musician Peter Broderick, who had written to him in celebration of continuous music. This meeting with the former Efterklang member led to the modern-classical dance producer Hauschka. Soon he met Robert Raths of Erased Tapes. Raths felt that Melnyk would fit with his label, and they agreed to release the album Corollaries.

Now Melnyk shares a label with the much-loved Nils Frahm, and Iceland's Olafur Arnualds, whose Kiasmos project reframes modern piano. Melnyk's lost but strangely futuristic music had finally caught up with a generation of open-minded musicians, yet this musician's quest is far from finished. "Every day I feel heavier and heavier and heavier to understand that I'm the only pianist in the world that can do this," he says. "That is a terrible thing… Let's just nail this on the head now. I was not struck by lightning suddenly from above and could play continuous music. People are scared of my technique and they shouldn't be. No one gave me fairy dust and sprinkled it on me and I could play 'Windmills.' It wasn't so sudden. It was more like a seed that grew… it was a flower that gradually opened up. And you can experience this as well. People just need to try."