Hackney Soldiers - The Birth of Jungle

Music Journalism

Hackney Soldiers - The Birth of Jungle with Shut Up and Dance

Hackney Soldiers - The Birth of Jungle

Shut Up And Dance vs The Ragga Twins: The rise of East London’s sound systems and the dawn of jungle.

Originally published in Clash Magazine

April 2011

Words by Matthew J Bennett

In 1970s London, the city council had all but abandoned the growing ghetto of Hackney. Cut socially adrift and left to their own devices the musical people of this maligned manor were largely a black community. Keen to instil the displaced and politicised music of reggae meant their modest house parties and church halls saw the bass seep into the grimy walls of their neighbourhoods around Stoke Newington, Clapton, Dalston and Hackney.

Sound systems vibrantly sprung in every area as reggae- and dub-obsessed men drifted together to form formidable powerhouses of hertz and taste. These rhythmic tribes were named directly after their heroes and godfathers back in Jamaica, buoyed high with their regal names of Sir Coxsone, Duke Reid and Sir Lord Emperor, these bass-heavy rigs explored the perimeters of their territory packing low-end anthems to battle, then slay their opposition (along with their loyal supporters) with the latest, most exclusive, most sizzling records – a war fought for reputation alone.

From this entrenched defiance in bass culture grew the foundations of future music genres. Whilst much has been said of Croydon’s role in the emergence of dubstep, twenty years ago Hackney was formulating one of dubstep’s key precursors. In 1989 crucial producers were chopping up the DNA of hip-hop, hardcore and house to give birth to something darker and more captivating: jungle

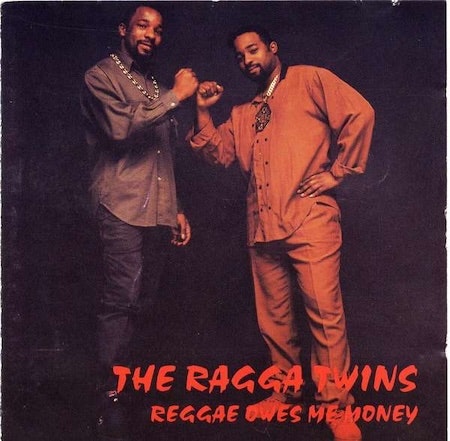

And it’s within this tangled patch of Hackney that we pick up the paths of two vivid musical pacts that helped develop then push that genre: the Destouche brothers of Flinty Badman and Deman Rockers – AKA The Ragga Twins – North London MCs whose dominance with Unity sound system saw them rise to the top of the sound clash ladder. Secondly, we have Philip ‘PJ’ Johnson and Carl ‘Smiley’ Hyman, two young ambitious friends who, in collusion with best friend DJ Hype, developed their own sound systems in the early ’80s before eventually recording and releasing as the sublimely effective unit Shut Up And Dance, and who many concede were the founders of jungle.

Two decades later, in their house in Stoke Newington, PJ and Smiley are reminiscing with Flinty Badman, who is currently deep in recollection about the 4Aces club, East London’s reggae focal point. Originally constructed in 1966 on the site of an old Victorian theatre built to house Robert Fossett’s Circus in 1886 on Dalston Lane, this was a place that allowed reggae to distil so deeply into the borough of Hackney and gave a fixed hub for the incalculable but always territorial sound systems.

“We’d go to The 4Aces all the time. Everyone did,” murmurs Flinty. “We used to go to one round the corner as well, it was like four times bigger, called Qubies, but it wasn’t known as well as the 4Aces at all.” Smiley, one half of Shut Up And Dance, is equally bubbling with history: “But if you think about it then there were bigger sound clashes in Qubies, it was [sound systems] Jah Shaka and Fatman all the time. It was reggae and soul really; 4Aces was for older people and Qubies was for younger people – it was way more skankin’.”

As captivated by the bass sounds as any black youth in the same ’hood, PJ and Smiley quickly got in on the action. In a spate of DIY that would see their influence stretch to this very day, they started their first sound system at an outrageously young age: “We’d not do the clubs obviously,” laughs Smiley. “We’d do venues, and do dances. We’d hire church halls. When we started we were a reggae sound system. It was me, my brother and DJ Hype. Our first gig was at a church hall at Lea Bridge Roundabout. We were actually twelve years old! We had one speaker box. DJ Hype made the flyer, he still has it on his wall.”

Clash is impressed. Twelve-year-olds putting on raves? “Nah! Don’t get excited! There was nobody there!” laughs Smiley. “We didn’t know what we were doing – but we just did it anyway, in 1982, and it was ALL reggae.” This first, fledgling rig was called Transistor Warrior, but it wasn’t long before the brothers had gradated to the grand tradition of employing a noble precursor to almost any name.

“We became Sir Lena, cos you always had to have a ‘Sir’ in front of everything. Sir Lena was around 1983, but my older brother, he was more of a soul head, and he used to go to these parties in West London and listen to people like Greg Edwards from Capital Radio, and he brought the soul influence onto me and my twin brother; he MCs now for Hype. So when we took the sound out on the road we were the only people rolling that soul sound with the hardcore reggae.”

Around the same time, slightly further north towards Tottenham, Deman and his brother Flinty were fighting their way up the MC battle hierarchy on a sound system called Jah Marcus. Their heritage (their family originated from Monserrat) gifted these brothers a blend of rough toasting with razor sharp observations and edgy aggressive lyrics.

But they wouldn’t be on Jah Marcus for too long. An ascendant collective called Unity, run by the now legendary Ribs (AKA Robert Fearon, a former soundman for the older Fatman system) came knocking in 1984. He was packing some firepower as well. Through his Caribbean connections, Ribs managed to get his Unity Sound sponsored by the dub lord Prince Jammy. With especially rude tunes and integrity from over the Atlantic they were a force to be respected – but little was ever easy. “It was tough,” remembers Flinty. “You got to battle your way from the bottom to the top, you’ve to battle a lot of sounds to get to the top and then when you get there someone will knock you down. It’s a constant battle all the time. Also you couldn’t go out every single weekend, you couldn’t chat the same lyrics; you’d need fresh lyrics every week.”

This is where our protagonists’ paths cross, as Smiley jumps in: “That’s because people were following you. I used to come see you all the time, they were older so I would go and I’d know Deman’s lyrics all the time. I knew him to say hello to, but he was like ‘The Big Man’ – he was like a ghetto celebrity, he really was.”

PJ and Smiley and the Destouche brothers wouldn’t work with each other until 1990 when the MC brothers left Unity Sound system. Also, PJ and Smiley were far too busy dominating the illegal party scene to think about making tunes. “We used to kick off the door of an empty house,” Smiley openly confesses. “My brother was an electrician; he’d get the lights working, then plan a rave for two weeks later. The houses we used to break into were like big town houses with five rooms and we’d pack them!”

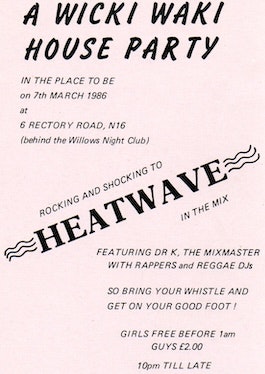

They weren’t alone. Around 1986 there were countless similar but semi-nomadic organisations, but this era also saw the rise of the soul systems, crews like Roxy Sound, Manhattan Soul Sound, Jazzy B, Rebel MC’s called Beatfreak Sound. But PJ offers up an explanation of why their sound (at this point called ‘Heatwave’) laid a blueprint that would see them mutate their format and sonic ideas toward the birth of jungle. “Basically all the UK sounds aspired to be like the Jamaicans; they’d play just the one thing, turn over the record and play the other instrumental side, and DJ over it, cos ‘DJ’ used to mean sing over it back in the mid-’80s. But we did things differently; we had two turntables and DJ Hype was cutting up reggae with hip-hop.”

At this point Smiley laughs as if he were still that teenager: “NO-ONE DID THAT! And me and PJ were behind DJ Hype with two mics – NO-ONE EVER had two mics! We used to perform! We wanted to do something different; we didn’t want to just hang back smoking weed. Reggae dances had this kind of slow thing to it. And we wanted it more energetic, so DJ Hype was cutting up reggae and hip-hop and my brother would be MCing over hip-hop, which you just wouldn’t get back then. No- one really understood what were doing; we just wanted to sound different. But we hit and missed ’nuff places. A lot of people just watched us.”

Most of the serious sound systems had a Jamaican sponsor – sometimes they were directly linked, as in the case of legends like Coxsone and Duke Reid, both powerful men from Kingston who allowed the UK collectives to be fed exclusive dynamite dubplates way ahead of the pack and increasing the chances of them winning a hotly contested sound clash.

In other cases the link was just as strong even if the names didn’t match. Prince Jammy was the patron of Unity, who for a while ruled with an absolute classic: “Jammy sent ‘Sleng Teng’,” grins Flinty. “So Unity was the first to play ‘Sleng Teng’! Jammy would send tunes pretty much every other week. All through the ’80s and ’90s loads of Jamaican sounds would come over and play the UK then go back. Every producer wanted a representative on the ground in the UK, but Ribs and Jammy was close anyway. Jammy would send sounds to other systems as well but he’d save all the best for Unity and the other sounds would get that record five weeks later or something.”

The rivalry this caused can’t be overstated enough. And there were many protagonists. Flinty takes us on a quick rundown of the geography: “Sir Lord Emperor was from Stoke Newington, active from the ’70s, they were all straight-up reggae. Quaker City were from Tottenham, they were more dub sounds but they used to clash with Fatman a lot, who were Tottenham also. Then there was Sir Biggs from Hackney, along with Sir George, Scrap Iron, and Godfather. Another one was called Surge in Dalston, who were like the youth sound; they did a hall on Holy Street that was ALWAYS packed – they had kids from EVERY school in there. Sometimes if you misbehaved and your mum wouldn’t let you out, then you just knew that EVERYONE would be at Surge and it’d be their highlight of the week.”

Smiley bounces in again: “I don’t think I missed one! We didn’t have a mum, she left us, so we were at every single one. This was through 1982/’83/’84. Then, by ’84, there were more dances in schools. There was one Tubby’s, a white guy – in fact probably the first white guy doing sound systems; he did dub sounds in homage to Tubby. Lots of the sound systems were an East London thing but Tubby’s – EVERYONE went.”

Luckily the rivalry only stayed within the music. There was never any significant violence or wounding, yet the aggression was so channelled it took over people’s lives, including these men. “That’s maybe why our mentality has remained the same with all the music,” ponders Smiley. “We still want to be the best, we only want to put out stuff that people can’t test, nothing that’s just ‘alright’. The whole era back then was very aggressive. There wasn’t any room to be losing battles; everyone would find out if you had lost a battle. You needed the best sound, the best records and of course the best MCs.”

We wouldn’t be doing these protagonists justice if we didn’t investigate some details, and Flinty happily supplies an anecdote from a significant battle. “I remember Philip Levi, he was a top MC, he really was the top of his game. He would go to a dance and when he got on the mic he would just start on someone – he would start running down [insulting] the other sound system. I remember I was chatting on a system called Gemmi Magic, just playing in a church hall called Reverberations. So he [Philip Levi] came in giving it loads of chat about everything, I just kept my head down, I didn’t say anything; I just thought it was a dance so I wasn’t prepared for a battle.”

“But he came back the following week,” he continues. “Same shit, running down the sound, chatting bad, but I was ready and I had one lyric for him. And it destroyed him. He came back on the mic, stuttered three times then gave up the mic. Even Tippa Irie came on after that but he couldn’t help; [the dance] was finished for the night. Phillip Levi only figured out later that I was Deman’s little brother. He understood then. After that he never clashed with us again.”

We’d been left hanging. What the fuck was the lyric? “Ah, course,” chuckles the MC. “So, Levi was a dread but he chopped his locks off, so I just said: “Philip Levi / A long time ago he was a Rastafari / But he could no stop with dem sausages and savole / He’s eatin’ dem wit the pigs in the sty!”” As Flinty laughs deep, PJ and Smiley whoop in delight too. This historical moment has seemingly lost none of its potency over two decades on.

It was yet more rivalry that spurred Shut Up And Dance on to release a record, which not only immortalised themselves on wax but also massively helped spawn jungle. No small claim! “We were doing the house raves as Heatwave around ’86 – it was about as popular as it was going to get with the youths,” says Smiley. “Then Soul II Soul brought out a record and that sent us into a spin. It was unheard of back then. So we were like, ‘We HAVE to put a record out!’”

After winning a competition for studio time, banging demos together with DJ Hype and recording in their bedroom on a four-track, they soon had (in their own words) “some fairly dodgy records”. Inspired by hip-hop and their heroes Run DMC, their music was fast, vocal and aimed at people’s feet. They tried to get signed to the biggest beats label at the time, G-Street, but failed spectacularly.

In hindsight PJ knows why. “No-one wanted to know because we were making rap but really sped up. Which is why people say we invented jungle: we were taking rap beats, speeding them up really fast then rapping over it because we were into dancing and body popping. We didn’t want slow rapping like the Beastie Boys or LL Cool J. We wanted something fast that you could dance to.” Smiley, as ever, agrees: “So we made our thing faster and that’s why we never got signed, because we didn’t fit with anything. The name Shut Up And Dance was the name from one of our demo plates. That was the name that summed us up: it was all about getting up and dancing and getting into the vibe.“

With continual knock-backs PJ and Smiley swore they’d succeed. Working in nine-to-five jobs, the pair were determined, but their early work was rough with some cute errors. Such moments are rarely more evident than on their early hit ‘£10 To Get In’. “Halfway through you hear my older brother come bang the door and shout, ‘Turn that down! It”s too loud!’” laughs Smiley.

Yet it wasn’t a proto jungle slab of vinyl that broke them. It was a raved-up house hybrid that layered aggro rap vocals over George Kranz’s hit ‘Din Da Da’ and Susan Vega’s ‘Tom’s Diner’ to make a magpie anthem that was perfectly embraced by the acid house arms. “We pressed five hundred records of ‘5,6,7,8’,” continues Smiley. “Then we took them up to the West End – that was like the Holy Grail to East End boys! They all sold out in a day!”

Lavishly now liquid in the vinyl world, PJ and Smiley instantly reinvested in the less commercial ‘£10 To Get In’, a beast of a track that heard them pitch up their US heroes’ hip-hop loops into a break-beat that was ideally timed to coincide with the national rave scene’s hunger for faster music as the drug ecstasy kicked in. It also laid the strongest blueprint yet for the jungle sound. From here they never looked back.

That was 1989, and within a year they’d have teamed up with Flinty and Deman, swiftly rebranding themselves The Ragga Twins before unleashing ‘Hooligan 69’, which broke into the Top 60 with its bleepy, break-beat and visceral ragga vocals. ‘Shine Eye’ and ‘Spliffhead’ in 1990 and 1991 respectively saw the combination of Shut Up And Dance and Ragga Twins sew up a rave sound that would carry their influence far, and one that eventually would mutate into UK garage.

So did SUAD in fact invent the name jungle? No. Jamaican MCs have been talking about ‘junglists’ from an estate nicknamed ‘The Jungle’ in Trenchtown for years, though legend has it that the UK adopted the name after Rebel MC sampled a dancehall track that chatted, “Rebel got this chant / Alla the junglists”.

But did Shut Up And Dance invent the music of jungle? Not alone, but there are very few who contributed so much at such a critical time. Obviously such historical moments at the birth of a genre belie the existence of a whole movement and such genesis is never truly isolated by a pair of hands.

Meat Beat Manifesto had dropped their ‘Radio Babylon’ in 1990, but SUAD had nailed out their ‘£10 To Get In’ just months earlier in Christmas 1989, whilst Rebel MC’s ‘Comin’ On Strong’ (though later in 1990), along with Lenny De Ice’s ‘We Are I.E’, are all seen as crucial points in Hackney’s fostering of jungle as its own two-headed, two-legged beast. One thing is for sure: no other producers of this first wave had the imagination, the stamina and the range of tunes to generate the thirty-odd classics SUAD managed, that still get hammered in clubs today.

Geography once more kicked in. As the boom/bust of the brief proper rave period was about to happen, Hackney again led the way with its warehouse scene, catering to way more crowds. “Well, the warehouse scene started in Hackney, it was all right here,” beams Smiley. “But the club scene kicked off when the Tories closed down the rave scene in ’92. We’d get booked to play through the label but we’d turn down most of those bookings and just send the Ragga Twins instead.”

Flinty remembers this time only too well: it was the age of the decline of the sound system, a spiral that leads us to today’s climate where there’s

rarely any clashes and the history is seeping away. “It’s a shame the sound system culture died out,” he laments. “The venues got too strong, and all the sound pollution laws came in, the pirate radio stations got in as well, they served the same purpose really. Then property got really big and important, so the clubs got rid of the sound systems, then the council got rid of the clubs.” Smiley shakes his head. “There used to be a club every hundred metres round here.”

But where one door closes another opens. And it was at this juncture Shut Up And Dance were already fiddling with their hardcore, jungle and house structures and helping shape the garage sound which would be the next massive shift after rave. We don’t really have time here for that third era of PJ and Smiley, but they produced more successful garage tunes than they care to talk about.

“We were proper producers then,” says PJ. “So we knew we could get our teeth into it and do something that the kids would still love. And they did. We conquered that scene. Any garage compilation that came out there’d always be at least one but probably two of our tunes on it every time.” “I have always said this,” Smiley rounds off. “Britain has had two explosions: rave and then garage. Everyone was raving, the whole country. Then drum and bass came, but that was a niche thing, a lot of people left and just went about their business. But when garage came out the whole country jumped on it again! Whether you liked pop music, or reggae or whatever, it was huge. And we were lucky enough to have been part of both those explosions.”