Jeremy Deller - Indelible Grace

Clash Magazine

Jeremy Deller's in Clash Magazine

Jeremy Deller - Indelible Grace

Indelible Grace

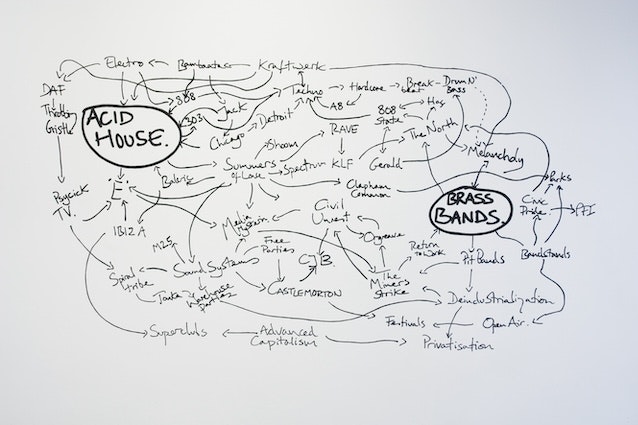

He’s crap at painting, and shit at sculpting, yet Jeremy Deller won the Turner Prize in 2004 with just a map of thoughts.

Originally published by Clash Magazine

Outsider Issue May 2012

Words: Matthew Bennett

Jeremy Deller is a modern maverick who thrives in uncomfortable situations. He dragged the exploded wreckage of a Baghdad car bomb around America to foreground a grim reality lost on TV. He insisted a brass band plays acid house anthems as an oblique unearthing of political subtext. Whilst many see his obsessive reenactment of the Miner’s Strike flash point ‘The Battle of Orgreave’ - replete with ten thousand actors, policemen and former miners in a brutal pitched battle - as his coup-de-grace.

But whichever way you look at his work, Deller demands your attention. His output as an artist is nebulous. He holds up tarnished history for us to never forget. He also prefers to operate far removed from London’s contemporary art circles, and whilst The KLF used to give £40,000 to the worst Turner Prize entry, his ‘History Of The World’ sketch, which helped him win the bone-fide art prize, somewhat ironically features the KLF anyway.

Clash finally pinned down this cultural curator whilst the noise of his first retrospective at The Hayward Gallery rages around his neat and blithely political thoughts.

One of the themes we’ve been studying in this issue is how much capitalist economies throw culture right into the middle and everything becomes homogenous via brands and television. How do you feel about that notion?

I suppose that’s always happened though hasn’t it? There’s plenty of fringe space for other people to operate and always will be. I’m not pessimistic about that, I know some people be. So, it’s always going to be the case. But there’s plenty of space for everyone else I think.

Do you think there’s enough space? As one of the leaders against the art cuts of 2010 do you think British expression is moving in the right direction or the wrong direction?

That’s a massive question. I think some of it is, some of it isn’t, really. I think it goes in both directions. It’s a mixture of things. I think there’s always going to be bad news stories, but I’m not worried because it gives us something to fight against or kick against. So I think it’s okay; you can be pessimistic about these things, but it’s easy being pessimistic. I don’t mind too much, it gives you something to kick against.

Do you think society’s expression was more singular during the uncomfortable social climate that you grew up under?

Yeah, well you grew up under Blair, didn’t you? Let’s face it, ’97...fifteen years ago...so, a lot of people who are ten years older than you, it was under a very different kind of regime. I’m forty-six. I grew up under ‘you-know-who’, so we had it differently. We all had the war in Iraq to deal with and that was something that was dealt with...that’s a huge thing, big as anything that happened in the ’80s really. It was a different climate, it was less friendly to the arts maybe. In the ’80s I think there was less opportunity.

As a youngster you were blessed with acid house. That’s been quite a consistent theme with your work from what I’ve seen. Would you say its effect on you was quite typical?

I wasn’t out there every weekend I have to admit, and I never pretended I was. But I was observing it more than taking part in it, especially initially. I wasn’t a committed person driving down the M25. But it was quite obvious quite quickly that it was culturally important as well as musically, and that was something I was interested in and still something that’s not as rated as it could have been compared to something like punk, which is much loved by the media because it’s still an outside music form compared to that.

Clash is always striving to find some form of political subtext in music but there’s been very little to grab hold of.

You have to remember acid house wasn’t really political, the songs weren’t political; from what I remember there was very little political message in it. It just became political because of the way it was treated. It became political by accident almost. It wasn’t political, where punk was clearly a message - most of the songs are instrumentals.

But with acid you took, discarded and marginalised communities and a folk form, then fused it with an insidious political type of music.

You see, I don’t think they’re marginalised. I mean it was a brass band, they’re a part of everyday culture. They’re not really marginalised. They’re not like hanging around on street corners those guys in the brass band. I don’t do that kind of art, actually. I think it’s just something that gets written about me, but I don’t see them as that to be honest. I think they’re more...they’re a sort of a subgroup of sorts, but they’re just regulars guys, you know. They’re not outcasts, they’re not outsiders in a way you think about outsider art.

But are they not symbolic in a way of a former community that’s been degraded?

Maybe, but they’re not degraded people in themselves. So many things are symbolic of that, but I don’t think...they’re not outsiders, I really don’t think they are, but you can read that into it, but it’s not the way everyone reads into it.

As an artist that’s quite involved in actions, when the youth riots happened in 2011 were you drawn to interact with it in any way?

No. In a way that’s not how I work, but...no. I was a bystander, metaphorically. I wasn’t interested in trying to make a piece of art about it immediately. So no, I was quite happy...not happy...I just saw it like we all did on TV.

What’s the difference between that, as a Londoner, and towing the car bomb wreckage from Iraq around America? You weren’t a bystander in Iraq.

You react to different things in a different ways. There’s no law or hard and fast rules about how you’re going to make work, it’s just an idea I had and was able to do. It’s something I was able to think about for a long, long time. So that’s probably why it wasn’t just a quick reaction to something, it came out of years of thinking about it.

You strike me - and this is a presumptuous statement - as a very political person.

Up to a point. I think that I’m interested, as we all are, in politics. I’m just an interested person; I’m not that involved in things that much, not on a day-to-day basis. But I have an interest in it, definitely. I’m just lucky that I can articulate it because of the work I do, the position I’m in.

Does it surprise you that in the music industry specifically, so few people with a voice are willing to use it to try and either improve other people’s situation or rage against some form of inequality?

You do what you can. I don’t think you should feel like you have to be critical in what you do. KLF were political; you couldn’t work out what that actually was, but it was just the way they did things. So it’s often the way you do things rather than what you say. I don’t think you can prescribe that people should be more like this and more like that, it’s really up to them, so I don’t look for that necessarily. I try not to look at things in those terms, because everyone has their own way of doing things really.

Do you ever wonder where the next political music movement might come from in Britain, or do you think that’s not going to happen anymore?

Sort of, but...I’m waiting for it. I’m not dying to wait for it. It’ll come when it comes, no point getting worried about it. It’ll happen, I’m sure. It’ll probably be surprising, I’m confident that something will happen.